Christian Rogers: Heaven on Earth

NOON Projects is pleased to present “Heaven on Earth,” a solo exhibition of works by Christian Rogers opening September 15, 2023.

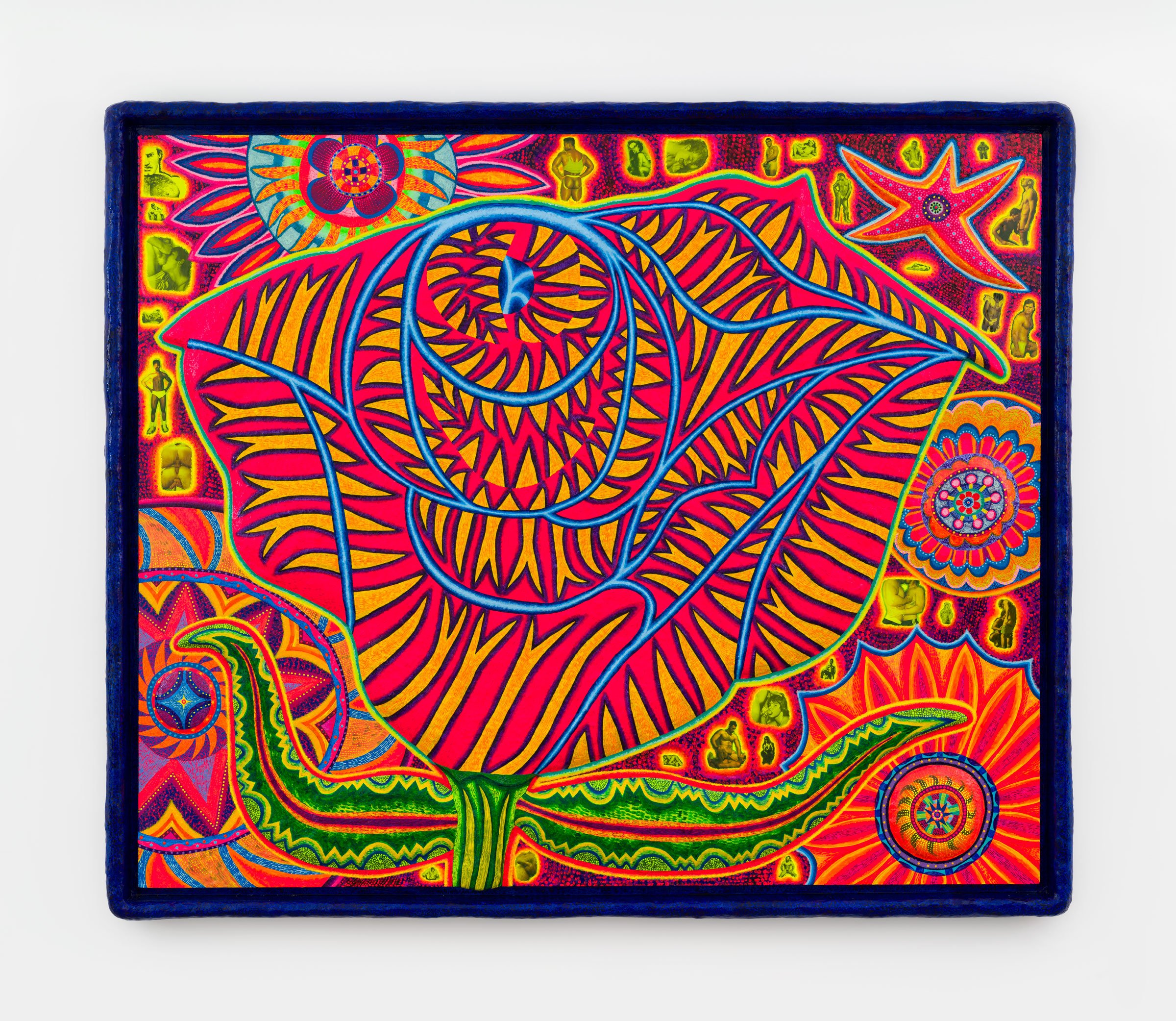

In his paintings, drawings, and photographs, Rogers constructs fantasias of queer joy through the gauzy, layered patina of vintage porn and its textured materiality. Vision and touch are thoroughly intertwined in the sexy solicitations of his hunky figures embedded in a vibrant landscape of cactus blooms, a landscape that Rogers has provocatively likened to the winding pathways of a cruising ground and its visual language of a subtle look or gesture.

Rogers translates the virtual mode of our contemporary engagement with erotic content through screens back into the material substrate of paper. These pictures invite their beholders to reorient their unconscious gestures across the glass surfaces of their phones—pinching, zooming, swiping—back into the world of flesh and blood. Most of these gestures can be traced back to techniques developed by illustrators in the pages of early magazines to solicit touch with seductive advertising. In Rogers’ pictures, old and new media—vintage porn and Grindr dudes—rub up against one another in a kind of scrapbooked palimpsest, one whose temporally vertiginous quality is telegraphed through the cinematic sparkle of a James Bidgood mise-en-scene crossed with the hallucinatory color palette of a Lisa Frank lunchbox.

Rogers’ paintings seem to formalize a kind of queer sensibility by cutting across the boundaries between painting and sculpture. A frame sculpted out of paper pulp and painted so that it is materially continuous with the rest of the picture challenges the traditional binary division between a picture and its frame, between what is “inside” and “outside” of the work: it is more pizza crust than parergon. Vivid planes of color coincide with the underlying substrate of magazine clippings and paper pulp that juts out from the surface in pulsating planes of low relief that mirror the pictorial projections of the ass up, big-dicked hunks in his lovingly curated collection of smut.

But if the naked men in Rogers’ pictures offer, despite their diminutive scale, the most titillating subject matter, they are dwarfed by the flowers in which they seem to float and frolic like fairies or horny satyrs on ancient Greek vases. Like many other flowers, cactus blossoms are bisexual, possessing both male and female sex organs. As art historian Alison Syme has shown, the “hermaphroditic” subjectivity of flora offered artists at the turn of the twentieth century such as John Singer Sargent a way to queer the poetics of painting (Sargent himself likened the act of painting to hand-pollination). Rogers pushes this secret history into the present and out in the open. Like the kind of intergenerational queer friendships he often cites as his inspiration, Rogers’ pictures offer a reparative vision of queer joy that is—and this might be the most shocking thing of all about them—not timeless but historical.